These Young Voting Activists Are The New Black Suffragettes

Vashti Hinton was a college sophomore in 2013 when she first realized what it meant to fight for her right to vote as a young Black woman. On the first day of class, she learned about House Bill 589, aka North Carolina’s “monster” voter suppression law. The bill removed early voting in the state, eliminated voting outside of one’s precinct, and required voters to show a very specific form of identification — all restrictions that would disproportionately affect Black voters. This was the first time Hinton had heard of the bill, and it rocked her perception of her right to vote. “As Black people, we have less voting rights now than we did back in the ‘60s,” she remembers thinking at the time. Seven years later, she’s working to change that as a voting rights activist, carrying on a long legacy of Black women’s voting activism.

Black women’s fight for political power has often been overlooked, both by history books and contemporary politicians. While popular histories of the fight for women’s votes highlight white leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Black women like Sojourner Truth and Ida B. Wells are often given short shrift. Additionally, histories of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, which fought for Black people’s right to vote, often focus on male leaders and overlook the crucial role of the women who took on the weight of community organizing, like Ella Baker. As the United States heads toward the August 2020 centennial of the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, not enough has changed. “Black women who do so much for their communities don’t get the honor they deserve,” says Hinton, now 25. “They show up heavy, not just for Black people but for all people, but they’re still overlooked. To what end?”

Hinton is now the college outreach coordinator at the nonprofit government watchdog and advocacy organization Common Cause, where she works with historically Black colleges and universities (known as HBCUs) to promote political education in communities of color. “Black and brown students aren’t usually the ones who, historically, have had access to this type of education,” Hinton explains, “and with that access comes power.” She says by helping other people of color learn more about politics, she’s building their influence on issues that matter to them. “We hope to introduce them to this world to show them how it works, but also teach them how they can reclaim and impact it themselves.” She works on campaigns like the End Gerrymandering Now initiative, which work for fair districts and voting maps.

Just as House Bill 589 — which was eventually killed by a federal court in 2016 for its discriminatory effect — would have suppressed the Black vote in North Carolina, various other states are still enacting policies that disenfranchise marginalized voters. Felon disenfranchisement laws, lack of polling machines, voter roll purges, and gerrymandering can make it difficult, and sometimes impossible, for many voters to cast their ballots. The restrictive policies often disproportionately affect communities of color.

“There is a lack of investment in the most vulnerable communities,” explains Arekia Bennett, the 27-year-old executive director of the non-profit voting rights organization Mississippi Votes. “A lot of folks don’t know the most basic stuff when it comes to participating in the electoral process.” Her organization works to mobilize the electorate through voter registration drives, fellowship programs for college students, and consistent community education. “Part of building what we are trying to build in the state of Mississippi is making this process as inclusive as possible for every person that wants to be a part of it,” shares Bennett. “We believe in the possibilities of democracy, and the possibility of a truly well-informed electorate.”

In Mississippi, saturated in the history of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Bennett sees the impact of the legacy of Black suffragettes and voting activists on her work every day. “Their wisdom is so accessible,” she says. “My staff is all Black women, and they always remind me of the women of our history. Annie Devine, Ella Baker,” she says. “We sit at the feet of our elders.”

For Alexis Campbell, an 18-year-old Youth Advisory Board member of Vote16USA, a national campaign to lower the federal voting age, pushing for change in her community is the best way to continue the legacy of fighting for Black women’s political power. “I’ve watched my peers’ — especially when they are also people of color — voices be discarded,” she says. “But I’ve also seen how an entire path can be changed just by having a simple voice.” She thinks many young people like her have missed out on resources that could educate them on their rights. “Learned helplessness is a big challenge for us,” she explains. “Some of my peers have this sense that there isn’t anything we can do or achieve, because they don’t even know where to start.” Campbell works to promote young voters’ political power via social media campaigns and civic education advocacy.

Black women have long been viewed as an electoral prize for Democratic politicians. In 2018, Black women voters were credited for the “Blue Wave” that gave Democrats control of the House of Representatives, and as of 2020 they are one of the most active voting blocs in the electorate. If turnout patterns follow previous years, in 2020, Black women will cast an expected 11 million votes, according to public policy think tank The Center For American Progress. “We expect a lot from Black women. People look at Black women to come and save everybody,” Hinton explains. “And we will always show up. Black women are continuing to do this work all over the country, but this is a huge weight for us to carry.” While Black women have become a valuable constituency for politicians, their support can be taken for granted by politicians who are always pursuing the white moderate vote. If politicians don’t want to continue a history of overlooking Black women, Hinton says, it’s important to focus on issues like food insecurity, affordable housing, and funding for education — all of which are currently affecting her own community.

While there’s more work to be done, there are some small indications that Black women are finally getting their due. In 2019, the New York City Public Design Commission approved a new monument to the women’s suffrage movement to be installed in Central Park, featuring famous suffragettes Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The design was met with wide and vocal criticism for the whitewashed representation of the fight for universal suffrage, and has since been amended to include Black suffragist Sojourner Truth seated alongside Anthony and Stanton. The statue is scheduled to be unveiled in August 2020, just in time for the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

For the leaders of today, the past and the future are intertwined. While they say they draw inspiration from the past, they credit their resolve and determination to their fellow young Black activists, and the next activists who will follow in their own footsteps. “We have a responsibility to the next generation to show them what is possible, and they are looking to us to advocate with them — not for them,” Bennett says. “We are going to do for them what the generations before did for us.”

More like this

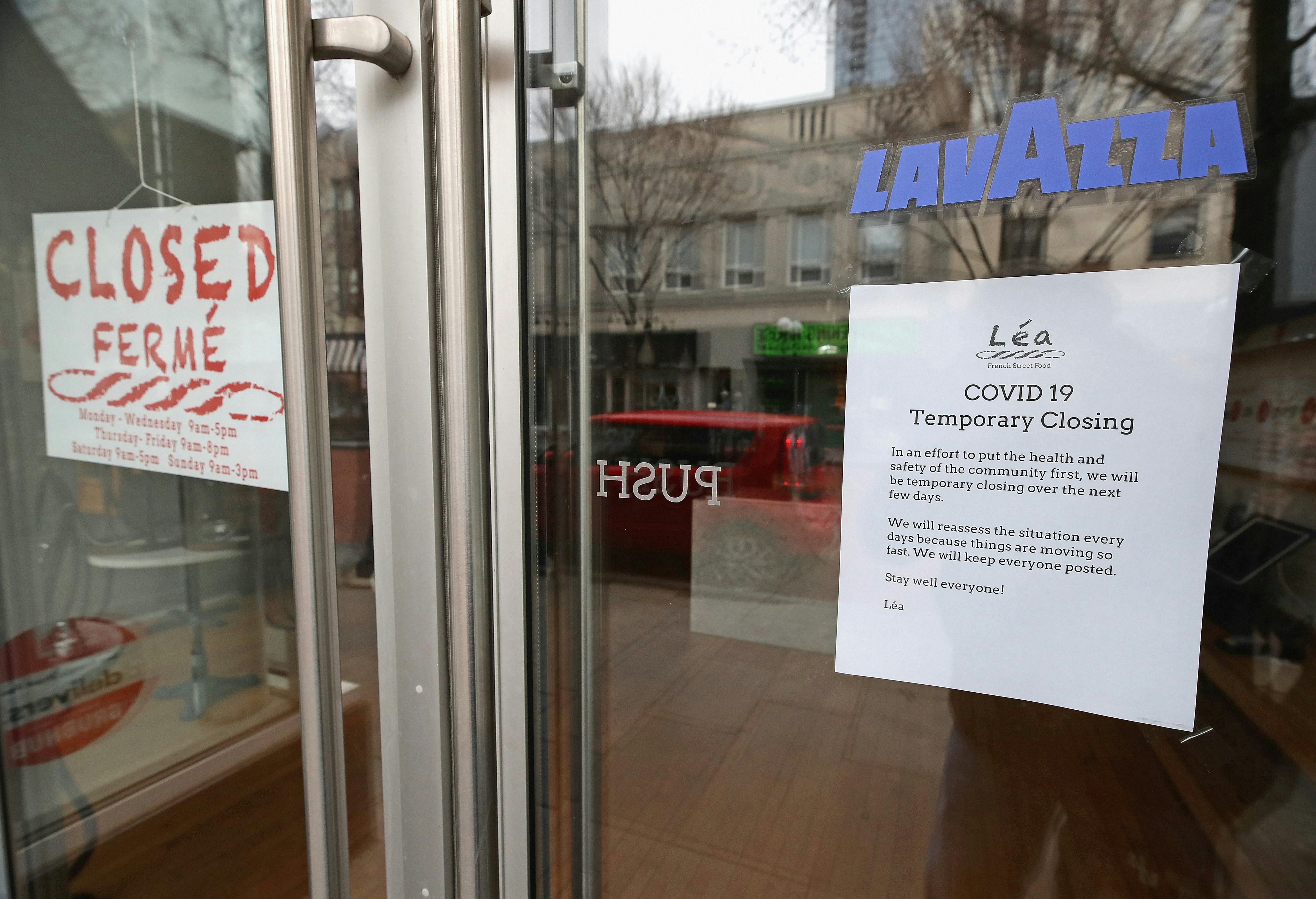

College Graduations Are Being Canceled Due To Coronavirus & Seniors Are Crushed

We’re On Coronavirus Lockdown In Italy. Here’s What We Want American Teens To Know Now

Here’s How To Help Laid-Off Shift & Gig Workers During The Coronavirus Pandemic

Stay up to date

Don’t miss a thing with the Elite Daily newsletter.

Source: Read Full Article